New Federal Energy “Corridors:”

Just What Are They?

Dr. Eric Karlstrom, Professor of Geography

Our federal energy policy is really a large trough arranged by the hogs for their convenience.

– Amory Lovins, Colorado energy expert, Mother Jones, 2008

We need an energy bill that encourages consumption.

– President George W. Bush, 2002

Introduction: 2005 Energy Policy Act Mandates New Energy Corridors

Energy, including electrical energy, is essential for civilization as we know it. Today, America gets some 54% of its electricity from coal power plants and another 22% from natural gas power plants. With the possible exceptions of the production and distribution of food and water, no human activity has a greater impact upon the environment, the economy, and the way we live than how we produce and distribute energy.

Electrical blackouts rolled through California in 2001 and swept from Ohio to Canada and New York City in 2003. These blackouts are mainly attributable to deregulation policies sponsored, for the most part, by Republican politicians for the benefit of the energy industry. The blackouts, in turn, were used by the Bush administration as justification for an energy bill which mandates that a consortium of federal agencies, in partnership with “stake holders” (like energy companies), designate a national network of energy corridors to solve this (created?) “problem.” The resulting Energy Policy Act of 2005 was passed when a re-elected President Bush claimed a “mandate” and Republicans controlled Congress. In addition to promoting the interests of the coal industry and investor-owned utilities over those of locally-generated energy and publicly-owned-utilities, this bill threatens private property rights, states’ rights, and millions of acres of already-protected federal and state land. Pepper Trail characterizes the new energy bill as essentially a “grab bag of tax breaks and incentives to various sectors of the energy industry that failed to raise vehicle mileage standards or take any other meaningful steps to reduce energy demand.”

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 mandates two new types of energy corridors: Section 368 instructs the Secretaries of Energy, Interior, Agriculture, and Defense to work with stakeholders (including energy companies) to designate two-thirds-mile-wide energy corridors for oil, gas, and hydrogen pipelines, electricity transmission lines, and other energy infrastructure on public lands. Each corridor could hold as many as nine electric transmission lines and 35 petroleum and 29 natural gas pipelines. The draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) for the West-Wide Energy Corridor indicates that this “corridor” would extend 6000 miles across eleven Western states and cover 3 million acres of federal land.

Section 1221 of the energy bill requires the Department of Energy (DOE) to identify areas of electricity congestion and permits DOE to designate National Interest Electricity Transmission Corridors (NIETCs) in order to resolve problems of electricity congestion. The bill also gives the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) authority to override state siting-authorities that might turn down or fail to approve an energy company’s proposed electricity transmission line within a year. Companies are permitted to use the government’s eminent domain authority to condemn private land to ensure new transmission lines are built or existing lines are expanded. In practice, DOE’s mandate to designate NIET corridors has been interpreted by DOE as giving them the power to designate whole regions of the country- even entire states- as energy “corridors,” though these bear little or no resemblance to “corridors.”

The West-Wide Energy Corridor

What’s 3,500 feet wide, 6,055 miles long and 2.9 million acres big? That’s wider than Hoover Dam, bigger than Yellowstone National Park and almost three times as long as the Mississippi River? This behemoth goes by the name of the West-Wide Energy Corridor, and if you live in the West it could soon devour a landscape near you.

Arising out of the political context of 2005, the Energy Policy Act did not entertain the possibility that energy use could actually be reduced through conservation, and it gave little consideration to local power generation by wind farms or solar arrays, for example, that would not require massive, long-distance energy corridors. In other words, the West-Wide Energy Corridor was never a prudent attempt to plan for the future: it simply takes a failed energy distribution model and makes it bigger.

So far, what appears to be a land grab has received little media attention.

– Pepper Trail, “An Energy Octopus Wants to Eat the West,” 2008

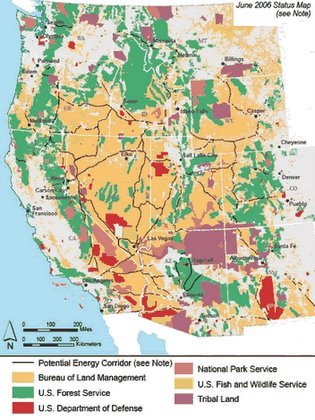

The West-Wide Energy Corridor designates 6000 miles of 2/3 mile-wide corridors that would cover about 3 million acres of federal land in 11 states, including Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, Montana, Nevada, California, Oregon, Idaho, and Washington (Figure 1). Note that a 2/3-mile-wide corridor would be the equivalent of nearly 12 football fields placed end to end!

Figure 1 West-Wide Energy corridor proposed in 2007 draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS)

Figure 1. West-Wide Energy corridor proposed in 2007 draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS).

In November, 2007, a 1,000+ page “West-Wide” draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) was released by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and thirteen cooperating agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the State of Wyoming. The document does not specify how DOE intends to extend the transmission corridors across state and private land. And it does not include project-specific activities at this time.

The West-Wide DEIS, dated October, 2007, was not published in the Federal Register until mid-November, at which point DOE initiated a 90-day public comment period. Because there was very little press coverage, many individuals, groups, counties, Indian tribes and even states were effectively shut out of the decision-making process. In “Energy Corridor Will Forever Alter Landscape of the West,” Grace Herndon reports that officials in San Miguel County, Colorado were not alerted to this plan until late 2007. She observes:

Now, apparently, it’s so critical to get this thing nailed down, that the plan is being fast-tracked… A path averaging 3,500 feet wide, taking up 6,000 miles and almost 3 million acres of public land alone– for what national purpose? The trouble is that local and regional organizations are still struggling to grasp the outlines of this sweeping land use proposal, which not only affects federal lands but the privately-owned land– the ranches and farms and the communities– which lie between those federal holdings.

Art Goodtimes, San Miguel County Commissioner, stated: “There has not been meaningful consultation with the states or the tribes about this process, and I’m here to tell you that there has not been meaningful consultation with counties either.” Of 159 counties affected by this process, only three had been granted cooperative status. “We need a comprehensive energy plan in this country but we need more time to do this right.”

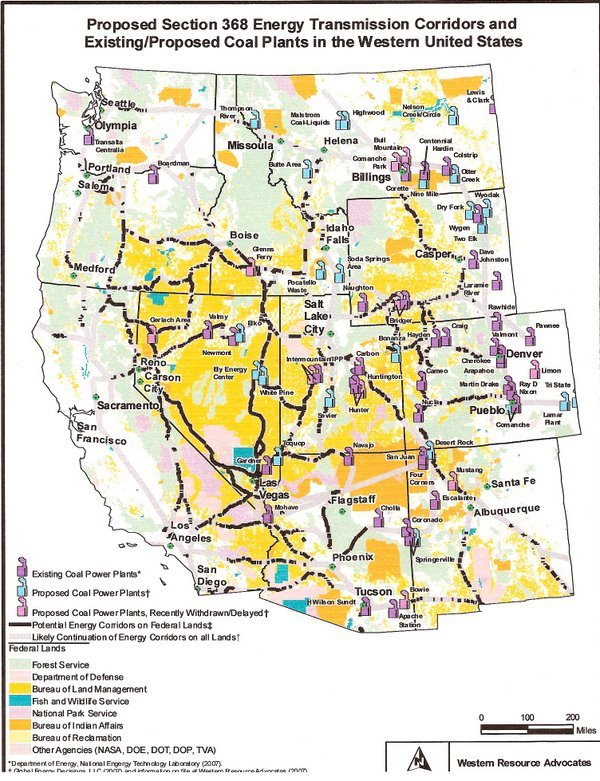

Representative Raul Grijalva (D-AZ), chairman of the subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands, stated: “(The Corridors) seem to act like huge extension cords to existing coal power plants with the opportunity through these corridors to make new coal power plants.” A Wilderness Society spokesperson agrees, noting: “The proposed energy corridors show the administration’s multi-billion dollar grid to be little more than a network connecting existing and proposed coal-fired power plants that bypass many areas rich in renewable energy potential” (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Relationship between proposed West-Wide energy corridors and existing coal-fired power plants (from Western Resource Advocates.)

Figure 2. Relationship between proposed West-Wide energy corridors and existing coal-fired power plants (from Western Resource Advocates.)

Similarly, Nada Culver of The Wilderness Society explained: “The corridor locations were created from an original “wish list” proposed by industry and bisect many important and sensitive places, including places that are designated conservation areas and would be expected to be protected from such intrusions.” The Wilderness Society’s analysis indicates that the proposed corridors threaten six national wildlife refuges, three national parks, seven national monuments and more than 60 current and proposed wilderness areas. Among the impacted special areas are the Havasu National Wildlife Refuge on the Arizona/California border, Joshua Tree National Park, California, Grand Staircase National Monument in Utah, New Mexico’s Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge and Arches National Park, Utah.

In “An Energy Octopus Wants to Eat the West,” Pepper Trail notes that the DEIS maps show that the West-Wide Energy Corridor would create:

…a network of cracks spreading across the West, from Puget Sound to El Paso, and from San Diego to the Little Bighorn. On these maps, our beloved West looks like a shattered and poorly mended dinner plate. And that is an entirely accurate image.

These new energy corridors – averaging six-tenths of a mile wide – will fracture a landscape that is already a maze of hairline cracks – the lines made by highways, railroads and the current, comparatively delicate energy rights-of-ways. These existing corridors have been enough to severely fragment habitat in the West, interfering with the movements of pronghorn, elk and bison, denying undisturbed wild areas to wolves and grizzly bears, and weakening the ecological health of deserts, grasslands and forest.

The West-Wide Energy Corridor, if enacted, would be the death sentence for many wildlife populations… One tentacle would split the Big Horn Basin of Wyoming; another would run the length of California’s Owens Valley between Sequoia and Death Valley National Parks; another would cut from Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado to Bandolier National Monument near Sante Fe. You have to wonder why the government didn’t simply use the existing system of energy corridors and rights-of-way. (http://www.redding.com/news/2008/jan/28/energy-octopus-wants-eat-west/)

Local citizens’ and environmental groups across the West are now fiercely opposing the West-Wide Energy Corridor. Judith Lewis (“Walking on a Wire” http://www.hcn.org/servlets/hcn.Article?article_id=17749) states:

The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance is fighting a transmission corridor that will plow a route along Utah’s Moab Rim. In Oregon, conservation groups oppose a proposed gas line that would bore under rivers in the Mount Hood National Forest. According to a map of the proposed transmission routes issued by the Dept. of Energy, the state of Nevada could be divided up like a quilt to transport energy straight through the Desert national Wildlife Complex. “No opening of any wilderness areas in this state to any energy corridors ever,’ Bill Huggins of Friends of the Nevada Wilderness told the Department. of Energy at a public meeting in Las Vegas. ‘Absolutely not.’

The Colorado portion of the DEIS maps show several main corridors. One runs east-west along Highway 50 from Grand Junction through Salida to just east of Pueblo, where it mysteriously stops. The major north-south corridor traverses western Colorado from Mesa Verde National Park in the south to near the northwestern corner of the state. Smaller corridor segments stretch across federal land from west of Denver to about Hot Sulfur Springs and from about Rifle north into southern Wyoming. Higher resolution maps reveal large gaps in the designated corridors where they cross state and private land. DOE, however, is not providing information regarding the likely locations of these connections to the public.

Pepper Trail notes:

Then there’s the contentious issue of property rights. On the maps, the lines representing the corridors are frequently interrupted, only to pick up again after a gap. Those gaps are private land; the map shows only the rights-of-way proposed for federal land. Obviously, those gaps must be filled in, and if you happen to be a landowner in the way, watch out!

Critics note that a fundamental problem with the West-Wide Energy Corridor DEIS is that it includes only one alternative- and this plan essentially calls for linking existing polluting coal power plants throughout the West. In this regard, DOE is in non-compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires that federal agencies “rigorously explore” and “evaluate all reasonable alternatives.” Western Resource Advocates asserts that DOE has not, but should, also consider these alternatives: 1) Reduce demand in population centers by increasing energy efficiency and the use of local power sources, 2) Focus the corridors on linking clean and renewable sources to the power grid, and 3) Maximize the use of existing power lines and substations through technology upgrades before designating new corridors. Tom Darin, energy transmission specialist for Western Resources Advocates, concludes: “Newly designated corridors must be ones that are needed, otherwise we will be unnecessarily carving up Western lands.”

Nada Culver of the Wilderness Society agrees, noting:

The Energy Department needs to seriously evaluate alternatives to minimize the number of corridors and maximize the use of renewable energy, and it should include requirements to presumptively limit all projects to designated corridors. The Energy Department has this one chance to get these corridors right and to improve access to renewable energies, such as wind and solar. With appropriate planning, they could address our transmission needs while also avoiding sensitive protected lands.

Incredibly, the draft EIS concludes that the corridors would not have environmental impacts. Nada Culver, states:

…. The proposed corridors still lack thorough consideration of the likely damage to federal lands and other places. The designations still don’t provide justification for the siting of corridors or information on the location and sources of energy to be moved through the corridors. The corridors can draw damaging development to areas where there might have only been a power line before. There are no exceptions for places already identified for protection, such as wilderness, wildlife refuges, parks and historical sites. This process will amend more than 160 land-use plans and permit projects with lesser reviews.

Also, the corridor designations would not preclude companies from proposing corridors and projects outside the corridors. Greg Trainor, utility and street systems director for the City of Grand Junction, Colorado, stated:

We are concerned generally with the broad swaths of land under the proposed action alternative and with the statement that, should applicants wish to apply for lands outside of the corridor, they may do so. That, combined with the “no effect” meaning… raises the question of the purpose of the corridor designation in the first place.

– The Mid-Atlantic Area National Corridor

On October 5, 2007, DOE published its orders designating two National Interest Electrical Transmission Corridors (NIETCs). These corridors are located in two of America’s most populous regions, purportedly in response to data and analyses that show consistent “congestion” in these regions. The Mid-Atlantic Area National Corridor encompasses 116,000 square miles (over 74 million acres) that include the metropolitan areas of Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City, as well as 47 counties in New York, 50 counties in Pennsylvania, all of New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, and large portions of Ohio, Virginia and West Virginia (Figure 3). Some 49 million Americans live within the affected area.

Figure 3 The designated “Mid-Atlantic National Area Corridor” (from www.maccec.org/)

Figure 3. The designated “Mid-Atlantic National Area Corridor” (from www.maccec.org/).

DOE failed to conduct an environmental impact statement of the proposed activity, as required by the National Environmental Policy Act. Nor did DOE consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to identify and mitigate effects to the 95 threatened or endangered species that would be affected by the mammoth project, as mandated by the Endangered Species Act.

Wes Gillingham, program director of Catskill Mountainkeeper, stated:

The designation of the mid-Atlantic NEITC, which covers an area from the Canadian border to West Virginia, will have devastating effects on the lives of people and prevent state and local governments from taking a critical look at proposals for power line construction. These are places completely inappropriate to site transmission lines, for both human health and ecological value reasons. These corridors amount to a handover of states rights to the private interests of power companies.

Andy Loza, executive director of Pennsylvania Land Trust Association, states:

Supporters of so-called “national interest corridors” should have to demonstrate that new transmission lines are the only reasonable solution to meeting energy needs before federally-sanctioned seizure of property is considered. We need an energy plan that both addresses our 21st century challenges and takes advantage of 21st century technologies. Local generation, demand-response and energy efficiency most likely can meet our energy needs faster and more cheaply than huge new power lines. And these technologies can meet our needs without harming communities.

The Mid-Atlantic Area National Corridor also includes 35 national park units, including Gettysburg National Military Park (PA), the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River (NY and PA), Shenandoah National Park (VA), Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical District (VA), and the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (ME to GA). In addition, the “corridor” would take in Antietam National Battleflied (MD), Monocacy National Battlefield (MD), C&O Canal National Historical Park (MD, WV, and DC), Schuylkill River National Heritage Area (PA), Delaware and Lehigh National Historic Corridor PA) and the proposed Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage Area (PA, MD, VA, and WV).

Thus, the National Parks Conservation Association recommends that DOE revise their plan so that: (http://www.npca.org/media_center/fact_sheets/energy_corridors.html)

1) new energy corridors and power lines avoid national parks and their respective scenic view-sheds and do not support the expanded use of polluting energy sources, such as coal;

2) The designation process comply with all applicable federal laws including the National Environmental Policy Act, the National Historical Preservation Act, and the Endangered Species Act;

3) Any approved energy corridors and power lines do not violate any relevant Park Service resource studies, view-shed analysis, and the requirements of Section 106 of the National Historical Preservation Act,

4) Designated energy corridors contain strong mitigation measures, to address adverse affects on view-sheds, water quality, wildlife habitat and corridors, and native plants.

The Mid-Atlantic Concerned Citizens Energy Coalition includes on its website (www.maccec.org) many affected parties’ petitions requesting that DOE reconsider their Designation Order for the Mid-Atlantic Area National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor. These include petitions by Maryland’s Governor Martin O’Malley, Delaware’s Lt. Governor John C. Carney, Jr., the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, New York Attorney General, Andrew M. Cuomo, the New York State Public Service Commission, The New York State of Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), Communities Against Regional Interconnect (CARI), Pennsylvania Governor Edward G. Rendell, Pennsylvania Majority Leader Bill DeWeese, Pennsylvania Senator J. Barry Stout, and Virginia Governor Timothy M. Kaine..

These letters and petitions are worth reading. The New York State Public Service Commission (NYSPSC) notes that in making its Designation Order, DOE relied on erroneous data in the ‘Congestion Report’ produced by its consultants, CRA International, Inc. Despite the fact that numerous reviewers, including NYSPSC, have called this report into question, DOE has not answered these concerns or verified the factual basis of the Report on which it has based its Designation Orders.

Similarly, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (NJBPU) questioned DOE’s August 8, 2006 congestion study that “identified an area stretching from Albany, New York to the Washington, DC metropolitan area, including all of New Jersey, as a “critical congestion area.” NJBPU had asked DOE to refrain from designating the Mid-Atlantic Area National Corridor, stating:

…. until after it has analyzed whether alternative measures, including energy efficiency, demand response, and clean local generation within the critical congestion area could relieve congestion more effectively, at lower cost, with less harm to the environment, with better assurance of the reliability and security of our electric supply, or with less vulnerability to uncertainties such as future fuel costs, future environmental requirements, and other variables.

…. (Thus), DOE erroneously designated the Mid-Atlantic Area National Corridor without complying with the requirement of Section 216(A)(2) to consider alternatives proposed by interested parties and affected States to address the congestion problems in the Mid-Atlantic Critical Congestion Area.”

Noting that “the designation of an NIETC has serious and far reaching implications for the sovereign interests of the States,” Virginia’s Governor Timothy M. Kaine and Attorney General Robert F. McDonnell stated:

… the Designation Order is contrary to law, in excess of DOE’s statutory authority, and fails to observe procedure required by law. Specifically, DOE failed to consult with Virginia in conduct of the congestion study that served as the basis for its NEITC designations, in contravention of its explicit legal obligation to do so. Therefore, DOE’s designation of the Mid-Atlantic Area NIETC is unlawful.

In his June 8 letter to DOE Secretary Bodman, Pennsylvania Governor Edward G. Rendell noted that the proposed Mid-Atlantic Corridor is so expansive that it is meaningless. He also questioned if FERC would adequately consider conservation, alternative technologies and different routes. Rendell stated:

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s ability to disregard a state’s evaluation of a proposed project challenges Pennsylvania’s rights. FERC may force Pennsylvania to accept projects that are far from the best choice. These transmission lines will be on our soil, depreciate our property values, but they may not benefit our consumers. This is simply unacceptable.

Similarly, Daniel Griffiths, head of Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Energy Innovations and Technology Deployment, questioned whether a corridor that includes 50 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties is realistically related to actual transmission options. He noted that the proposed routes bypass parts of Pennsylvania where clean, new generation is coming online, and instead pulls power from old, dirty plants to the east and south of the state.

Maryland’s Governor Martin O’Malley also expressed concern about the expansive geographic scope of the draft designation, noting that 1) the NIETC encompasses an enormous geographic area, encompassing nearly all the State of Maryland and thus, is far from a “corridor,” as that term is commonly understood, 2) the designation appears to go beyond the intent of the 2005 Energy Policy Act, 3) a much more refined corridor designation may be appropriate, 4) DOE failed to make adequate efforts to work with the State of Maryland and its citizens in studying and formulating solutions to electric transmission congestion, and 5) DOE failed to property consider non-transmission solutions to congestion and constraint issues.

In his appeal for DOE to conduct a rehearing, John C. Carney, Lt. Governor of Delaware wrote:

.. (the proposal) runs counter to forward thinking energy policies to promote sustainable “green” energy alternatives that are right for Delaware and the nation. It also hinders the goal of increasing local energy generation to improve reliability and protect consumers from future price shocks like the one Delaware experienced earlier in this decade. And the proposed new corridor does nothing to reduce energy demand, either through improved efficiency of infrastructure or conservation. By linking the coal-fired electric generation plants to our west with the high-demand mid-Atlantic region, this plan will create more dependence on heavily polluting sources of electricity at a time when we should be promoting cleaner alternatives.

According to the State of New York, the Federal Power Act (FPA), as amended by the Energy Policy Act of 2005:

changed the balance of power between State and Federal jurisdiction in the field of energy transmission… creating a new scheme of federal regulation over traditionally-exercised State authority related to siting and approval of electric transmission lines.

This petition also points out that the federal government is in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Act of 1996, all of which mandate consultation with other federal and state agencies:

Prior to issuing the Designation Order, DOE did not prepare or issue for public notice and comment an environmental assessment (“EA”) describing the proposed designation as required by its own NEPA regulations. Nor did DOE conduct an environmental impact statement (“EIS”) as required by NEPA and its own regulations… Furthermore, the Designation Order is beyond DOE’s authority under Section 216 and the APA.

DOE’s response to these requests for a rehearing or reconsideration of their Designation Order was to issue an Order Denying Rehearing on March 11, 2008 (http://nietc.anl.gov/documents/docs/Order_Denying_NIETC_Rehearing.pdf ). Thus, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this plan was hatched in secret by a cabal of industry/government insiders in defiance of numerous federal and state laws for the benefit of energy companies. Because the plan violates federal law, the U.S. Constitution, States’ rights, and private property rights, it clearly comprises a crime against the American people.

Currently, eleven national and regional environmental organizations, led by the National Wildlife Federation, are filing suit against DOE over its final designation of the Mid-Atlantic National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor (http://www.depweb.state.pa.us/news/cwp/view.asp?Q=533025&A=3&ppp=12&n=1). The groups are challenging the designation on the grounds that DOE violated the National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act by failing to study the potential harmful impacts of the corridor on air quality, wildlife habitat and other natural resources.

The suit also claims that DOE violated the requirements of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 by: 1) defining boundaries which extend far beyond the areas where transmission congestion or capacity constraints are alleged to occur, 2) the “Congestion Study” upon which corridor designation is purportedly based was procedurally flawed because DOE failed to consult with affected states before finalizing it, and 3) in the Designation Order, DOE failed to consider non-transmission or other alternatives. Finally, the suit charges that DOE designated the corridor without taking into account the potential effects on historic properties or engaging in the consultations mandated by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

Randy Sargeant Neppi, National Wildlife Federation lawyer, explained:

The Department of Energy has ignored the public interest in favor of the private interests of power companies. Our federal government should be working to find solutions that protect our natural heritage and promote a clean energy future so that our children and grandchildren will have a healthy communities, clean air and abundant wildlife and wild places to enjoy. DOE has failed to do even the basic due diligence and analyze responsible and cost effective alternative ways of meeting the region’s energy needs. Efficiency and conservation should be the first order of business…. The mid-Atlantic corridor designation puts and enormous area of the region at risk while sending our energy policy a major step backwars towards continued reliance on coal-fired generation.

– The Southwest Energy Corridor

It’s not a corridor. It’s an entire area of the country.

– Diane Conklin, southern California resident

It’s hard to see which Western constituency could possibly support this. But the answer of course, is that the constituency that supports this doesn’t live in the West. It lives on Wall Street and in C.C. and it is attempting, essentially… to sell off as much of our public land as possible for energy development before public outcry rises to the degree that such policy choices will not be tolerated.

– Amy Atwood, Center for Biodiversity Management

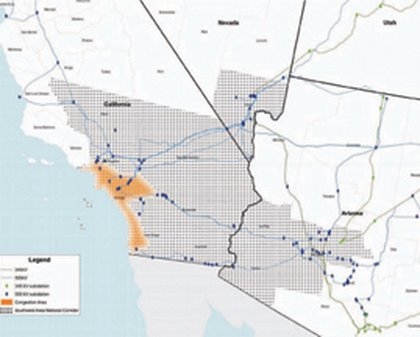

On October 5, 2007, DOE also designated the Southwestern Energy Corridor as another NIETC that would encompass the Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas and Phoenix metropolitan areas as well as large portions of southern California, Nevada, Arizona. Specifically, this “corridor” would encompass 70,000 square miles (44.8 million acres) that includes, seven counties in southern California, three counties in southwestern Arizona (Figure 4).

Figure 4. DOE’s designated Southwestern Energy Corridor in southern California, southern Nevada and southwestern A

Figure 4 DOE’s designated Southwestern Energy Corridor in southern California, southern Nevada and southwestern Arizona

rizona.

The 45-milion-acre ‘corridor,” drawn to include urban areas where electricity is needed as well as outlying areas where power is produced, stretches from the Mexican border to well north of Los Angeles and east to Phoenix. It includes 3 million acres of national parks, monuments and national wildlife refuges including Joshua Tree National Park, the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge, Sonoran Desert National Monument, and Carrizo Plain National Monument. This vast “corridor” also includes 21 million acres of the California Desert Conservation Area, 750,000 acres of BLM national monuments, and a part of the Las Californias, an internationally recognized biodiversity hotspot that is home to hundreds of protected or rare species. Altogether, the designated “corridor” includes 7.5 million acres of federally designated wilderness, wilderness study areas and citizen-proposed wilderness. And it includes at least 95 species that are listed as endangered or threatened with extinction under the Endangered Species Act.

Since this is also a National Interest Electrical Transmission Corridor, when utilities propose transmission lines and state regulatory agencies either reject them or put off action for long periods, they can ask the federal government to step in and review those projects. Thus, for example, San Diego Gas and Electric could become the first utility in the nation to ask the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to intervene in what has traditionally been a state process for evaluating projects. And again, if FERC were to approve the utility’s application, it could impart eminent domain authority to SDG&E, a private corporation, to condemn private lands needed for the project.

Brent Schoadt of the California Wilderness Coalition stated:

This proposal threatens to undermine years of conservation efforts to protect the California Desert Conservation Area and other wild places throughout the state.

As in the Mid-Atlantic Corridor, DOE failed to do an environmental analysis or environmental impact statement, as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). On January 11, 2008, the Center for Biodiversity Management (CBM) filed suit in federal court in California to challenge DOE’s designation of the Southwestern Electric Transmission Corridor. The lawsuit, filed by the Western Environmental Law Center, charges that DOE failed to analyze environmental impacts of the proposed corridor as required by NEPA. According to the Western Environmental Law Center, the DOE designation of the Southwest electrical transmission line corridor that allows for “fast track” approval within the corridor is an attempt to nullify state and federal environmental laws and enable energy companies to condemn private land for new high-voltage transmission lines.

Amy Atwood, of the Center for Biodiversity Management, stated:

The Energy Department cannot turn southern California and western Arizona into an energy farm for Los Angeles and San Diego without taking at hard look at the environmental impacts of doing so.

DOE has determined that these designations will remain in effect until October, 2019 unless the designations are rescinded or renewed.

– Comparisons with the Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC)

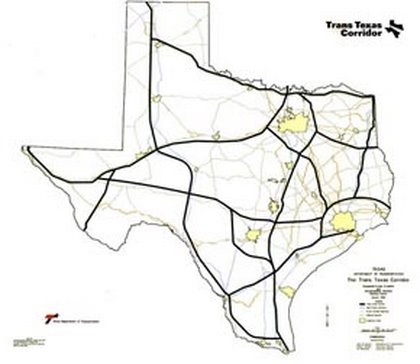

Just what are these new proposed corridors and who would benefit from them? The proposed West-Wide energy corridors are almost three times wider than the proposed 1200’-wide Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC), which is part of the “NAFTA Superhighway” that would extend from southern Mexico to Canada. NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), of course, is a series of trade agreements and treaties between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico that passed the U.S. Congress via “fast-track” in 1994. The North America Super Corridor Coalition, Inc. (NASCO) website shows the NAFTA superhighway extends from Lazaro Cardenas, Mexico to Kansas City, and into Canada, where it branches out to Vancouver on the west coast and Montreal in the east (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Artist’s conception of the “NAFTA Superhighway”

Figure 5. Artist’s conception of the “NAFTA Superhighway.”

In The Late Great U.S.A.: The Coming Merger with Mexico and Canada, Jerome R. Corsi notes that the 4000-page Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the TTC reveals that the 1200’-wide complex involves 10 lanes of highway, with five lanes in each direction, of which 3 lanes are for passenger vehicles and 2 lanes are for trucks. The EIS also includes 6 rail lines running parallel to the highways, with separate rail lines in each direction for high-speed rail, commuter rail, and freight rail. The design also calls for a 200’-wide utility corridor that includes pipelines for oil, natural gas, and water, cables for telecommunications and data, and electricity towers (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Texas Department of Transportation drawing of proposed TTC

Figure 6. Texas Department of Transportation drawing of proposed TTC.

Certainly, if all these transportation and energy facilities can be contained within 1200,’ one must question the need for 3500’-wide corridors. Like the West-Wide corridors, the TTC is designed to be an alternate to the existing interstate system. Indeed, it is to be a separate toll-road that abandons the existing interstate structure without attempting to supplement it. Under Republican Governor Rick Perry, TxDOT (Texas Department of Transportation) has contracted the construction and maintainence of the TTC to a Spanish multinational corporation, Cintra Concessiones de Infraestructures de Transport – or “Cintra”) which is forming a partnership with the San Antonio-based, Zachary Construction Corporation. According to Corsi, the TTC the beginning of a continental network designed to move inter-modal goods that derive from global trade.

Whereas the West-Wide energy corridor would carve up 11 Western states with some 6000 miles of 3500’-wide corridors, the TTC calls for building 4000 miles of highway/railway/utility superhighways in Texas over next 50 years at a cost of $184 billion. The 4000 miles of TTC criss-cross Texas and circle every major city, including San Antonio, Austin, Houson, and Dallas-Fort Worth (Figure 7).

Figure 7 4000 miles of projected TTC in Texas

Figure 7. 4000 miles of projected TTC in Texas.

Like the West-Wide energy corridor, the TTC will cut communities in half; people will have to drive tens of miles to get to the nearest overpass to see a neighbor or get to the other side of their ranches. And like the West-Wide energy corridor, the TTC will involve wholesale confiscation of Americans’ private property. According to Corsi, it will involve about one million eminent domain notices and will destroy some 584,000 acres of what is now farm and ranchland. These farms and ranches have produced food for America for generations. In Supreme Court case Kelo v. City of New London (545 U.S. 469 (2005), the Supreme Court decided that eminent domain could be used to seize private property from U.S. citizens even though the purpose of the land seizure was to benefit a private corporation. The decision says nothing that specifies that the corporation need be a U.S. corporation. In addition, a Texas state law (HB3588) allows a “quick-take seizure” of private property “if TxDOT (Texas Department of Transportation)and the property owner cannot reach an agreement” on just compensation for the land involved. Under current Texas state law, TxDOT can seize a property on the 91st day after the landowner is served with an official notice of quick take.

Similarly, according to the Energy Policy Act of 2005, after DOE designates a NIETC, when utilities propose transmission lines and state regulatory agencies either reject them or put off action for over a year, the utilities can ask the federal government to step in and review those projects. Thus, for example, San Diego Gas and Electric, a private corporation, could ask the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for eminent domain authority to condemn and seize the private lands needed for the project.

The size and scale of the Mid-Atlantic and Southwest NIET corridors, far surpass those of the West-Wide Energy Corridor or the TTC. Under their Designation Orders, DOE now claims federal dominion over 186,000 square miles (nearly 120 million acres) of land in the two most populous regions of the nation. These so-called “corridors” encompass large portions – or all- of 11 different states and all of the nation’s capitol. About one sixth of the American population lives within these so-called “corridors.” And a number of state governors are justifiably questioning the real purpose of these so-called “corridors.”

Finally, and perhaps most revealingly, the new energy corridors and the TTC were all railroaded into law in an extremely anti-democratic manner, through stealth and secrecy, and in violation of many existing state, local, and federal laws. Each of these projects seem to have involved essentially Soviet-style central planning with no meaningful democratic participation from ordinary citizens or even from Congress. They are proceeding against the will of the American people. All of these projects are direct attacks on private property, state’s rights, and the U.S. Constitution. As such, these projects seem to be intended to hand over vast portions of America to a relative handful of multinational corporations.

Dr. Jerome Corsi makes the case in his book, The Late Great U.S.A., that the TTC is part of the larger corporate plan to merge the U.S. with Canada and Mexico in a North American Union. Such a merger would destroy the U.S. Constitution and the civil liberties that Americans have enjoyed for over two centuries under the Bill of Rights. If we value our country, our democracy, and our U.S. Constitution, we would be well advised to get informed and organized, and defeat these “corridor” projects as presently defined. We can find solutions to these and other perceived problems that do not jeopardize the U.S. Constitution or the sovereignty of the American people, state’s rights, and the American republic.

Authors postscript: I began graduate work in Geography at the University of Wyoming in 1975. In an independent project for a course entitled “Geographic Location Analysis,” I used sophisticated computer programs to determine the optimal location of coal-fired power plants in the West. Because the costs of energy losses through long-distance transmission lines are considerably greater than the costs of transporting coal by train, it turns out that the most cost-effective place to site coal-fired plants is where the power is actually needed, i.e., in Los Angeles, Phoenix, Las Vegas, etc. But of course, then as now, state pollution laws prohibited this and so dirty coal power plants were sited, instead, in some of the most pristine areas in the West where the air quality was still excellent. It seems this very fundamental lesson has still not been learned by the energy industry or by the American people.